𝑻𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝑶𝒃𝒔𝒄𝒖𝒓𝒆 𝑶𝒃𝒋𝒆𝒄𝒕 𝒐𝒇 𝑫𝒆𝒔𝒊𝒓𝒆 (1977)

Introducing That Obscure Object of Desire (1977): Luis Buñuel’s Final Masterpiece

Overview

That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), directed by the legendary Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel, is a provocative and surreal exploration of desire, obsession, and the elusive nature of love. Adapted from Pierre Louÿs’s 1898 novel La Femme et le Pantin (The Woman and the Puppet), the film marks Buñuel’s final work, capping a career that spanned over five decades and revolutionized surrealist cinema. Starring Fernando Rey as Mathieu, a wealthy widower, and featuring two actresses—Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina—alternating in the role of the enigmatic Conchita, the film blends dark comedy, psychological drama, and political allegory. Set against a backdrop of terrorist bombings in 1970s Europe, this French-Spanish co-production, with a runtime of 103 minutes, is celebrated for its innovative narrative structure and Buñuel’s subversive genius. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the film’s plot, cast, production, themes, reception, and cultural significance, situating it within Buñuel’s oeuvre and the broader context of world cinema.

Plot Summary

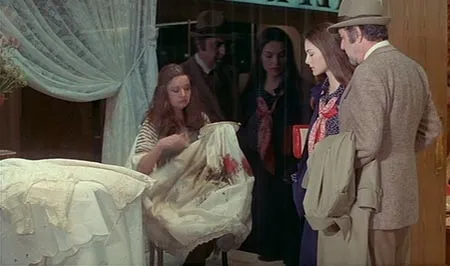

That Obscure Object of Desire follows Mathieu Faber (Fernando Rey), a sophisticated but aging French widower, who becomes infatuated with Conchita, a young Spanish woman he meets while traveling. The story unfolds through Mathieu’s recounting of their tumultuous relationship to fellow train passengers, framed by a memorable opening scene where he dumps a bucket of water on Conchita (Carole Bouquet/Ángela Molina) from a train window, signaling the end of their affair.

Mathieu first encounters Conchita as his maid, captivated by her beauty and flirtatious demeanor. Their relationship evolves into a maddening cycle of seduction and rejection, as Conchita alternates between promising love and withholding physical intimacy, frustrating Mathieu’s desires. She dances flamenco in a Seville bar, accepts his financial support, and even shares a bed, but consistently evades consummation, claiming to preserve her virginity. Mathieu’s obsession deepens, leading him to lavish gifts and money on Conchita and her mother (María Asquerino), only to be humiliated when Conchita spends a night with a younger lover, witnessed through a barred gate.

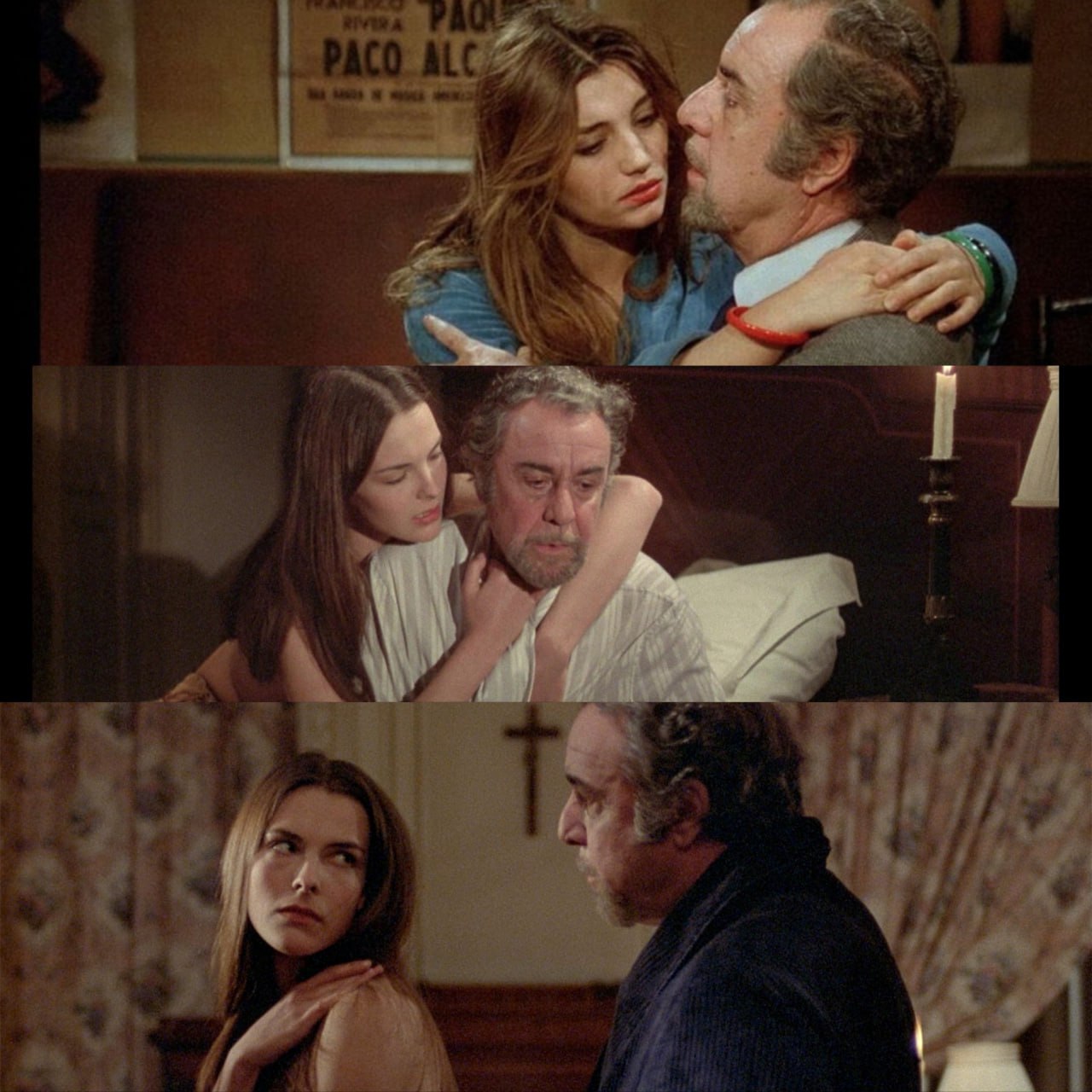

As Mathieu pursues Conchita across Spain and France, their power dynamic shifts. Conchita’s dual portrayal—Bouquet’s cool elegance contrasting Molina’s fiery passion—underscores her enigmatic nature, leaving Mathieu (and the audience) uncertain of her true intentions. The backdrop of random terrorist bombings, reported on radio and television, adds a layer of surreal unease, mirroring the chaos of Mathieu’s emotional turmoil. The film’s climax sees Mathieu and Conchita reunited in Paris, only to be caught in a bomb explosion while window-shopping, a darkly ironic end that leaves their fate ambiguous. Buñuel’s narrative, rich with surrealist touches, challenges viewers to question the nature of desire and the futility of possession.

Cast and Characters

Fernando Rey, a Buñuel regular (Viridiana, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), delivers a nuanced performance as Mathieu, blending aristocratic charm with desperate obsession. At 60, Rey captures the character’s vulnerability and patriarchal entitlement, making Mathieu both sympathetic and flawed. The innovative casting of Conchita, played by Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina, is central to the film’s impact. Bouquet, in her debut, brings a detached, ethereal quality, while Molina, known for Spanish cinema, exudes earthy sensuality. The actresses alternate unpredictably, sometimes within the same scene, reflecting Conchita’s mercurial nature and Buñuel’s surrealist intent to destabilize perception.

Supporting roles include Julien Bertheau as a judge and fellow train passenger, who listens to Mathieu’s tale, and André Weber as the valet Martin, adding dry humor. Milena Vukotic appears as a train passenger, and María Asquerino plays Conchita’s manipulative mother. The dual casting of Conchita, initially a pragmatic solution after actress Maria Schneider left the production, became a stroke of genius, earning praise for its psychological and thematic depth.

Production and Direction

Directed by Luis Buñuel at 77, That Obscure Object of Desire was produced by Serge Silberman, who collaborated with Buñuel on his late-career French films. Shot in Paris, Madrid, and Seville, the film had a modest budget, relying on Buñuel’s minimalist style and sharp storytelling. The screenplay, co-written with Jean-Claude Carrière, adapts Louÿs’s novel while infusing it with Buñuel’s surrealist trademarks: dreamlike sequences, anti-bourgeois satire, and a critique of patriarchal power. The decision to use two actresses for Conchita emerged after conflicts with Schneider, with Buñuel and Silberman embracing the concept as a way to embody the character’s duality.

Cinematographer Edmond Richard (The Discreet Charm) employs a muted color palette, contrasting the vibrant Spanish settings with the sterile elegance of Paris, enhancing the film’s psychological tension. The absence of a traditional score, replaced by ambient sounds and occasional flamenco, underscores the narrative’s raw emotionality. Buñuel’s direction is precise yet playful, with surreal touches—like a sack Mathieu carries, symbolizing his burdens—woven seamlessly into the realist framework. The film’s production faced minimal censorship, a testament to Buñuel’s established reputation, allowing its provocative themes to remain intact.

Themes and Style

That Obscure Object of Desire is a meditation on the futility of desire, the battle of the sexes, and the absurdity of human obsession. Buñuel portrays Mathieu as a bourgeois patriarch whose wealth and status cannot secure Conchita’s love, critiquing male entitlement and the commodification of women. Conchita, by contrast, wields her sexuality as both weapon and shield, embodying a feminist resistance to possession, though her motivations—love, manipulation, or survival—remain ambiguous. The dual casting amplifies this ambiguity, suggesting Conchita as a projection of Mathieu’s fantasies or a multifaceted enigma.

The film’s surrealist style is evident in its non-linear storytelling, unexplained terrorist bombings, and symbolic imagery, such as a torn lace curtain or a bleeding virgin statue. These elements reflect Buñuel’s lifelong fascination with the subconscious and his disdain for societal norms. The political subtext, with bombings alluding to 1970s European unrest (e.g., ETA in Spain, Red Brigades in Italy), adds a layer of social commentary, framing personal obsession against collective chaos. Stylistically, the film balances dark comedy with tragedy, its 103-minute runtime maintaining a brisk pace while allowing for introspective moments.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its release in August 1977 in France and October in the U.S., That Obscure Object of Desire was met with critical acclaim. It holds a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes (based on 25 reviews), with critics praising Buñuel’s wit and innovation. Roger Ebert called it a fitting capstone to Buñuel’s career, noting its “complex and audacious” exploration of desire. The film earned Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Adapted Screenplay, a rare honor for Buñuel, and won awards from the National Society of Film Critics.

Audiences were initially divided by the film’s surreal elements and explicit content, including Conchita’s nude flamenco performance, but its reputation has grown over time. On Letterboxd, it averages 4.0/5, with fans lauding its “perverse and hilarious” tone and the dual-Conchita device, though some find the terrorism subplot jarring. The film’s influence is evident in later works exploring obsessive love, such as Pedro Almodóvar’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989), and its casting innovation inspired films like Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There (2007).

Available on platforms like Criterion Channel, Amazon Prime, and Kanopy, That Obscure Object of Desire remains a staple in arthouse cinema, with Criterion’s Blu-ray release offering restored visuals and insightful extras. Its legacy lies in its fearless dissection of human desire and Buñuel’s ability to blend surrealism with social critique, cementing his status as a cinematic icon.

Cultural and Historical Context

Released in 1977, That Obscure Object of Desire reflects the cultural and political turbulence of the era. Europe was grappling with terrorism, from Basque separatism to left-wing militancy, which Buñuel incorporates as a surreal backdrop, echoing his earlier anti-fascist works like The Exterminating Angel (1962). The film’s Spanish elements—flamenco, Seville’s streets—evoke Buñuel’s roots, while its French setting aligns with his late-career exile, blending cultural identities.

The feminist movement of the 1970s informs the film’s gender dynamics, with Conchita’s agency challenging traditional roles, though some critics argue her character reinforces stereotypes of the “manipulative seductress.” Buñuel’s atheism and disdain for the bourgeoisie permeate the narrative, critiquing Mathieu’s privilege and the societal structures that enable his pursuit. As his final film, That Obscure Object serves as a summation of Buñuel’s themes: the irrationality of desire, the absurdity of power, and the liberation of the surreal.

Conclusion

That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) is a masterful swan song from Luis Buñuel, blending surrealism, dark comedy, and psychological depth to explore the enigma of desire. Fernando Rey’s poignant performance, paired with the groundbreaking dual casting of Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina, creates a hypnotic portrait of obsession against a backdrop of societal unrest. While its provocative content and ambiguous ending may challenge some viewers, the film’s wit, visual elegance, and thematic richness make it a cornerstone of world cinema.

Available on Criterion Channel and other platforms, That Obscure Object of Desire invites audiences to grapple with its questions about love, power, and identity. As Buñuel’s final work, it stands as a testament to his enduring genius, proving that even in his twilight years, he remained a cinematic provocateur unafraid to probe the obscure corners of the human heart.