Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun

Introducing Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun: A Provocative Dive into Nunsploitation Cinema

Introduction

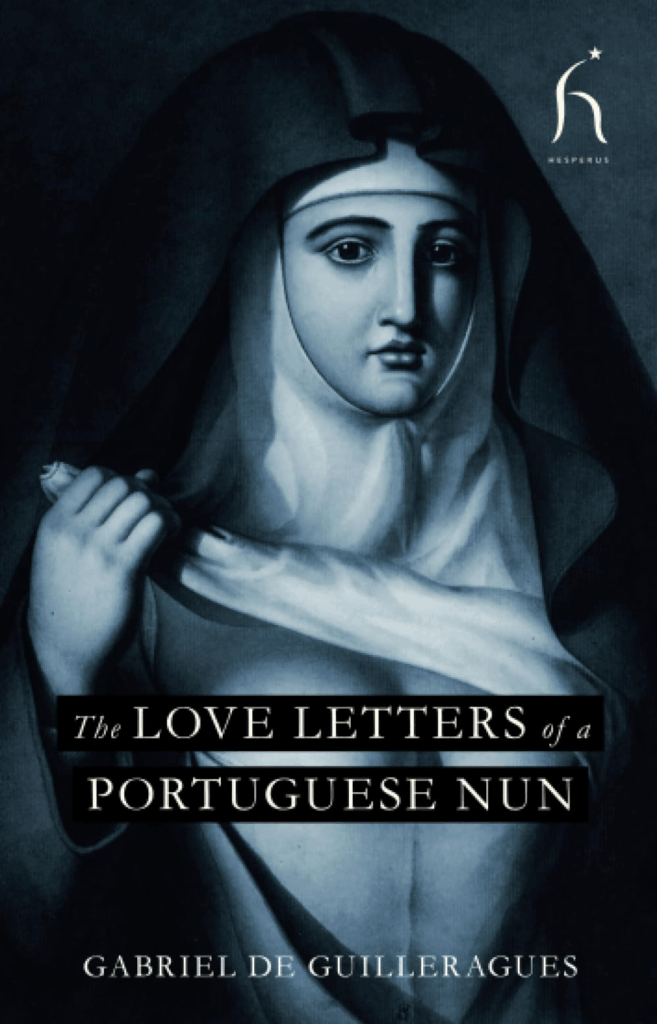

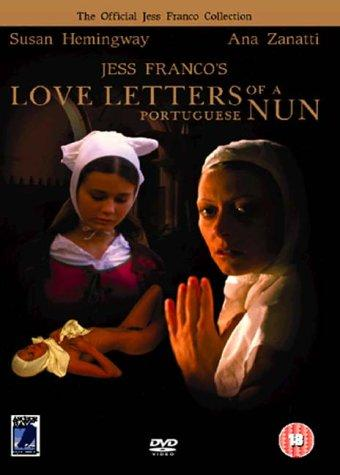

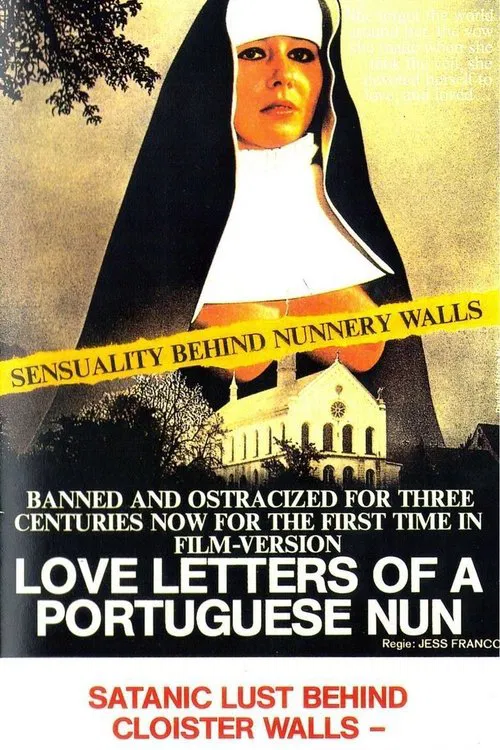

Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun (German: Die Liebesbriefe einer portugiesischen Nonne), released in 1977, is a West German-Swiss film directed by the prolific and controversial Spanish filmmaker Jesús Franco. Produced by Erwin C. Dietrich and loosely inspired by the 17th-century epistolary work Letters of a Portuguese Nun, attributed to Mariana Alcoforado, the film is a hallmark of the nunsploitation subgenre—a niche category of exploitation cinema that explores themes of sexuality, religion, and power within the confines of convents. Starring Susan Hemingway, William Berger, Herbert Fux, and Ana Zanatti, the film blends horror, drama, and *** to create a provocative narrative set in Inquisition-era Portugal. While polarizing due to its explicit content and controversial themes, the film remains a significant piece of Franco’s oeuvre and a fascinating artifact of 1970s exploitation cinema.

This article provides a detailed exploration of Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun, delving into its plot, historical and literary roots, production context, thematic elements, critical reception, and its enduring legacy within the nunsploitation genre.

Plot Summary

Set in an unspecified period of Portugal’s Inquisition era, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun follows the tragic story of Maria Rosalea (Susan Hemingway), a 16-year-old girl caught in a moment of innocent affection with her boyfriend by the sinister Father Vicente (William Berger). The priest, wielding his religious authority, convinces Maria’s devout and easily intimidated mother (Aida Vargas) to force her daughter into the Serra D’Aires convent as penance for her perceived sin. Unbeknownst to Maria and her mother, the convent is a façade for a secret sect of Satanists led by Father Vicente and the Mother Superior (Ana Zanatti).

Once inside the convent, Maria is subjected to a nightmarish ordeal of psychological manipulation, physical torture, and *** *** at the hands of the priest, the Mother Superior, and other members of the convent. The film’s narrative escalates as Maria is coerced into *** rituals, including encounters with a figure representing the Devil himself. Throughout her suffering, Maria is told that her experiences are merely a dream, blurring the lines between reality and nightmare. In a desperate act of faith, Maria writes a letter to God, casting it into the wind in hopes of salvation. A knight briefly rescues her, offering a glimmer of hope, but her escape is short-lived as she falls into the hands of the Inquisition, facing torture on the rack and condemnation to death by burning, reminiscent of Joan of Arc’s fate.

The film’s narrative is deliberately ambiguous, leaving viewers questioning whether Maria’s experiences are real, a hallucination, or a critique of religious hypocrisy. This ambiguity, combined with its shocking imagery, makes Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun a challenging yet thought-provoking cinematic experience.

Historical and Literary Context

The film’s title and loose inspiration come from Letters of a Portuguese Nun, a collection of five passionate love letters published in Paris in 1669. Initially believed to be authentic correspondence written by a Portuguese nun, Mariana Alcoforado, to her French lover, a soldier named Noël Bouton, Marquis de Chamilly, the letters are now widely regarded as epistolary fiction, likely authored by French publisher Claude Barbin. The letters, steeped in romantic longing and emotional intensity, became a literary sensation in Europe for their raw exploration of forbidden love and devotion.

However, Jesús Franco’s adaptation takes significant liberties with this source material, using it as a mere starting point. While the original letters focus on personal and emotional turmoil, Franco’s film pivots to a sensationalized narrative rooted in the nunsploitation subgenre, emphasizing horror, , and critiques of organized religion.. The film’s connection to the literary work is tenuous, primarily evoking the idea of a nun’s inner conflict while amplifying it with exploitation elements such as Satanism, torture, and sexual deviancy.

The nunsploitation genre itself has roots in earlier cinematic works, such as the 1911 silent film The Life of a Nun, which introduced themes of religious repression and forbidden desire. By the 1970s, nunsploitation films had become a staple of exploitation cinema, particularly in Europe, with titles like The Devils (1971) and The Nun of Monza (1969) exploring similar themes of religious hypocrisy and sexual transgression. Franco’s film, however, pushes these boundaries further, incorporating graphic content and a condemnatory stance toward the Catholic Church’s historical abuses.

Production and Direction

Directed by Jesús Franco, a filmmaker known for his prolific output and boundary-pushing style, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun was produced by Swiss exploitation mogul Erwin C. Dietrich. Franco, often referred to as “Uncle Jess” by fans, was a polarizing figure in cinema, celebrated for his bold vision and criticized for his low-budget aesthetics and reliance on shock value. With over 200 films to his name, Franco’s work spans horror, erotica, and avant-garde cinema, often blending genres to create unique, if controversial, experiences.

Shot primarily in Portugal, the film benefits from its stunning locations, including a monastery and a castle, which lend an authentic and atmospheric backdrop to the story. Unlike many of Franco’s later works, which were hampered by low budgets and excessive use of zoom lenses, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun showcases a more restrained and polished visual style. The cinematography, credited to Peter Baumgartner, is noted for its careful composition and lyrical quality, with lush forest scenes and cold, imposing stone interiors enhancing the film’s gothic tone.

The production was not without its challenges. Reports suggest that Dietrich, the producer, insisted on additional nude scenes to heighten the film’s commercial appeal, leading to the inclusion of *** shots that some viewers find distracting. Despite these interventions, Franco’s directorial touch is evident in the film’s ability to balance *** elements with a critique of religious corruption, making it one of his more cohesive works from the late 1970s.

The cast includes Susan Hemingway as Maria, delivering a performance that conveys innocence and vulnerability, and William Berger as Father Vicente, whose portrayal of the sleazy, hypocritical priest is both chilling and memorable. Ana Zanatti’s Mother Superior and Herbert Fux’s supporting role add to the film’s unsettling atmosphere, though the English dubbing in some versions has been criticized for detracting from the performances.

Themes and Style

Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun is a quintessential nunsploitation film, blending themes of religious hypocrisy, *** repression, and power abuse with horror and erotic elements. At its core, the film is a scathing critique of the Catholic Church’s historical abuses, particularly during the Inquisition, when religious authority was often wielded to control and oppress. Franco portrays the Church as a corrupt institution, equating its representatives with damnation rather than salvation. Father Vicente’s use of confession to gratify his desires and the convent’s secret Satanist rituals underscore this condemnation, highlighting the hypocrisy of those who claim moral superiority.

The film also explores themes of innocence and victimhood through Maria’s character. Her journey from a carefree teenager to a tortured convent novice evokes sympathy and underscores the brutality of the patriarchal and religious systems that ensnare her. The ambiguity surrounding whether her experiences are real or a dream adds a layer of psychological complexity, inviting viewers to question the nature of reality and the psychological toll of oppression.

Stylistically, the film stands out within Franco’s filmography for its measured pacing and careful cinematography. Unlike his later works, which often relied on frenetic zooms and low-budget aesthetics, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun employs a more deliberate visual approach, with beautifully shot scenes that contrast the natural beauty of Portugal with the horror unfolding within the convent. The film’s use of subdued color palettes and naturalistic lighting enhances its gothic atmosphere, while the involving *** content—, torture, and Satanic imagery—pushes it firmly into *** territory.

Reception and Controversy

Upon its release, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun was met with polarized reactions. Its graphic content, including *, and scenes of ***, led to censorship bans in some regions, delaying its release for two years in certain markets. The Catholic Church, particularly in Spain, condemned the film, with some labeling Franco as one of the most dangerous filmmakers of his time due to its blasphemous and provocative content. Critics were divided: some dismissed the film as exploitative and tasteless, while others praised its artistic merits and bold critique of religious institutions.

Contemporary reviews highlight the film’s duality. On one hand, it is celebrated for its visual beauty and strong performances, particularly Hemingway’s portrayal of Maria and Berger’s chilling Father Vicente. On the other hand, its explicit content, including scenes involving a minor (Hemingway was reportedly 15 or 16 during filming), has sparked ethical concerns and discomfort among viewers. Some reviews note the film’s ability to transcend typical *** fare, with outlets like Rotten Tomatoes describing it as having a “lyrical charm” and “entertaining quality” despite its simplistic plot and dubbing issues. Others, however, find the plot slow and the acting uneven, with some viewers on platforms like Letterboxd called it “morally wrong” yet “perfect” in its *** excess.

The film’s place within the nunsploitation genre has cemented its cult status. Fans of Franco’s work and exploitation cinema appreciate its blend of horror, eroticism, and social commentary, while detractors argue that it prioritizes shock value over substance. Regardless, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun remains one of Franco’s more ambitious and visually striking films, often cited as a standout in his extensive filmography.

Legacy and Availability

Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun occupies a unique place in the history of exploitation cinema, particularly within the nunsploitation subgenre. Its blend of horror, eroticism, and religious critique aligns it with other controversial films of the era, such as Ken Russell’s The Devils and Walerian Borowczyk’s Behind Convent Walls. The film’s influence can be seen in its ability to provoke discussion about the intersection of religion, power, and sexuality, even as its *** content continues to polarize audiences.

The film has been released in various formats over the years, including a digitally restored and remastered DVD by Full Moon Features, which presents the uncut 89-minute version in a widescreen 1.85:1 aspect ratio. A 2014 German Blu-ray release further enhanced the film’s visual quality, showcasing its detailed cinematography. It is available for streaming on platforms like FlixFling and Amazon Prime Video, with options to rent or buy. The Blu-ray release includes extras such as cast and crew interviews, a featurette, and a photo gallery, offering fans insight into the film’s production.

Conclusion

Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun is not a film for the faint of heart. Its *** content, provocative themes, and unflinching critique of religious hypocrisy make it a challenging watch, yet its visual beauty, strong performances, and bold narrative choices elevate it beyond mere exploitation. Directed by Jesús Franco at the height of his creative powers, the film remains a fascinating, if controversial, entry in the nunsploitation genre, inviting viewers to grapple with its unsettling portrayal of power, faith, and human suffering. For those willing to engage with its complexities, Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun offers a haunting and thought-provoking cinematic experience that lingers long after the credits roll.