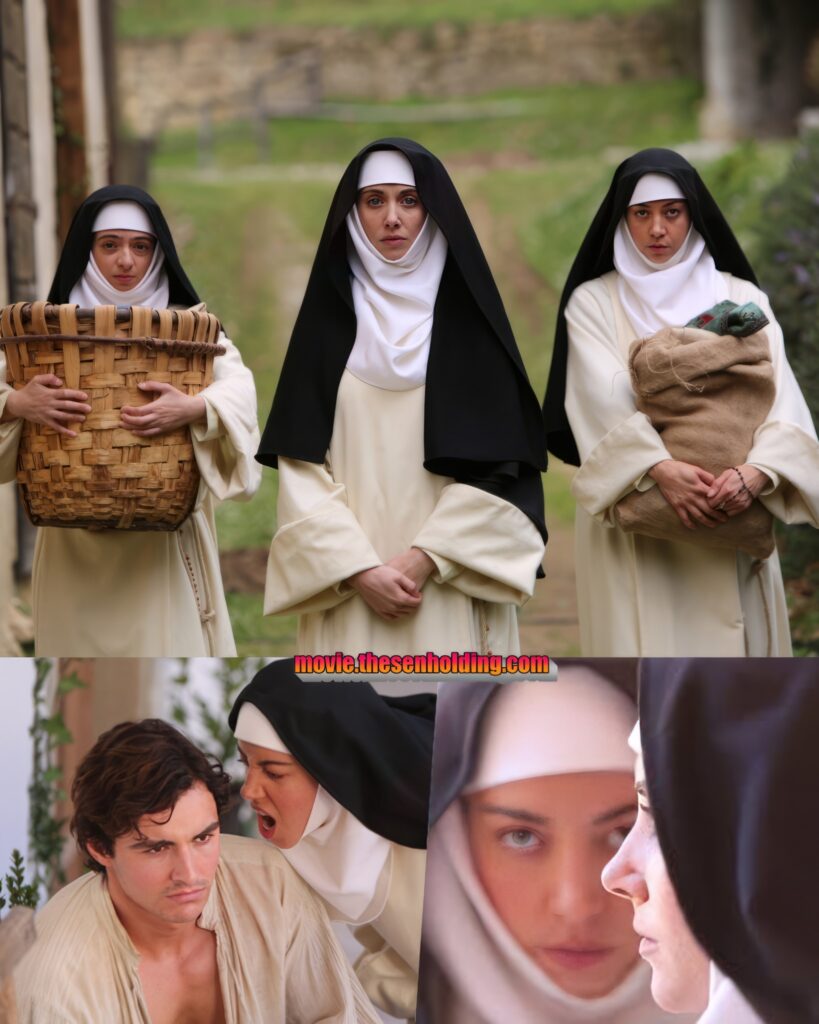

THE LITTLE HOURS (2017)

A Raunchy Romp Through the Middle Ages: A Comprehensive Review of The Little Hours (2017)

The Little Hours, directed by Jeff Baena and released in 2017, is a delightfully irreverent comedy that transplants modern humor into a 14th-century Italian convent. Loosely adapted from Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, this indie gem combines bawdy humor, sharp performances, and a subversive take on religion and repression. With its stellar ensemble cast, including Alison Brie, Aubrey Plaza, and Dave Franco, the film offers a fresh spin on period comedy, blending anachronistic dialogue with a surprisingly poignant exploration of freedom and desire. This review examines the film’s narrative, characters, themes, technical craftsmanship, cultural significance, and lasting appeal, making a case for why The Little Hours remains a standout in the landscape of modern comedy.

Plot and Narrative Structure

The Little Hours is set in a remote Italian convent in 1347, where three young nuns—Sisters Alessandra (Alison Brie), Fernanda (Aubrey Plaza), and Ginevra (Kate Micucci)—chafe under the monotony and strictures of monastic life. Their days are filled with mundane chores, petty rivalries, and suppressed frustrations, overseen by the weary Father Tommasso (John C. Reilly) and the stern Sister Marea (Molly Shannon). The arrival of Massetto (Dave Franco), a handsome servant fleeing his former master, Lord Bruno (Nick Offerman), disrupts the convent’s fragile equilibrium. Posing as a deaf-mute to avoid detection, Massetto becomes the catalyst for a series of chaotic, hilarious, and surprisingly heartfelt events.

The narrative, written and directed by Jeff Baena, draws inspiration from two tales in Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a 14th-century collection of novellas known for their wit and social commentary. However, Baena reimagines these stories with a modern sensibility, infusing the dialogue with contemporary slang and improvisation that feels jarringly anachronistic yet oddly fitting. The film unfolds as a series of comedic vignettes, punctuated by moments of farce, romance, and even surreal mysticism, all building toward a climax that balances absurdity with emotional resolution.

At 90 minutes, The Little Hours is tightly paced, allowing each character’s arc to shine without overstaying its welcome. The plot’s episodic nature mirrors the structure of The Decameron, with subplots involving forbidden desires, mistaken identities, and rebellious acts weaving together seamlessly. While the film prioritizes humor over historical accuracy, its loose adherence to its source material allows it to explore timeless themes in a way that feels accessible and engaging. The narrative’s unpredictability, driven by the characters’ impulsive decisions, keeps viewers entertained while offering just enough depth to elevate it beyond mere slapstick.

Characters and Performances

The ensemble cast of The Little Hours is a comedic powerhouse, with each actor delivering a performance that balances exaggerated humor with genuine humanity. Baena’s decision to cast comedians and indie darlings creates a vibrant dynamic, enhanced by the improvisational nature of the dialogue.

- Alison Brie as Sister Alessandra: Brie brings warmth and vulnerability to Alessandra, a nun who dreams of a life beyond the convent’s walls. Her performance captures the tension between duty and desire, with her deadpan delivery and expressive eyes stealing many scenes. Alessandra’s arc, rooted in her longing for love and autonomy, provides the film’s emotional core.

- Aubrey Plaza as Sister Fernanda: Plaza’s Fernanda is a force of nature—sardonic, rebellious, and unapologetically chaotic. Her sharp wit and unpredictable energy make her the film’s standout, whether she’s hurling insults or plotting mischief. Plaza’s ability to blend menace with charm ensures Fernanda is both hilarious and oddly relatable.

- Kate Micucci as Sister Ginevra: Micucci’s Ginevra is the convent’s nervous, eager-to-please outsider, whose awkwardness masks a surprising wild streak. Micucci’s comedic timing and physicality shine, particularly in scenes where Ginevra’s repressed desires bubble to the surface. Her performance adds a layer of endearing weirdness to the ensemble.

- Dave Franco as Massetto: Franco plays the hapless Massetto with a mix of charm and bewilderment, making him the perfect foil for the nuns’ antics. His chemistry with the leads, particularly Brie and Plaza, grounds the film’s more outrageous moments, while his subtle reactions amplify the humor.

- John C. Reilly as Father Tommasso: Reilly’s portrayal of the bumbling, wine-loving priest is both hilarious and sympathetic. His hangdog expression and knack for understated comedy make Tommasso a lovable figure, even as he fumbles his duties.

- Molly Shannon as Sister Marea: Shannon brings quiet authority and warmth to Marea, serving as the convent’s moral compass. Her scenes with Reilly are particularly touching, offering a glimpse of tenderness amid the chaos.

Supporting roles, including Nick Offerman as the bombastic Lord Bruno, Fred Armisen as a judgmental bishop, and Jemima Kirke as a free-spirited visitor, add further color to the ensemble. The improvisational approach allows the actors to play to their strengths, resulting in dialogue that feels spontaneous and authentic, even when it’s deliberately anachronistic. The chemistry among the cast is palpable, creating a sense of camaraderie that makes the convent feel like a dysfunctional but oddly endearing family.

Themes and Symbolism

The Little Hours is, at its heart, a satire of repression, religion, and societal expectations. By setting a raunchy comedy in a medieval convent, Baena cleverly juxtaposes the rigidity of religious life with the messiness of human desire. The film critiques the ways in which institutions—whether 14th-century convents or modern systems—seek to control individual freedom, particularly for women. The nuns’ rebellious acts, from sneaking wine to pursuing forbidden romances, are framed as assertions of agency in a world that seeks to confine them.

Gender dynamics play a central role, with the film highlighting the limited options available to women in the Middle Ages. Alessandra’s longing for marriage, Fernanda’s defiance of authority, and Ginevra’s struggle to fit in reflect different responses to patriarchal constraints. Yet the film avoids heavy-handed messaging, using humor to underscore its points without preaching. The anachronistic dialogue serves as a bridge between past and present, suggesting that these struggles remain relevant today.

The film also explores the tension between spirituality and carnality. Rather than mocking religion, The Little Hours portrays faith as a complex, often contradictory force in the characters’ lives. Moments of mysticism, such as visions and rituals, are treated with a mix of sincerity and absurdity, adding a surreal layer to the narrative. The convent itself becomes a symbol of both confinement and possibility, a space where rules are enforced but also subverted.

Visually, the film uses the lush Italian countryside and the stark convent interiors to reinforce its themes. The vibrant greens of the landscape contrast with the drab stone walls, mirroring the characters’ inner conflicts between freedom and duty. Recurring motifs, like wine (a symbol of indulgence) and the convent’s bell (a call to order), add subtle depth to the storytelling.

Direction and Technical Craftsmanship

Jeff Baena’s direction is confident and playful, embracing the film’s low-budget constraints to create a lean, focused comedy. Having previously directed indie films like Life After Beth (2014), Baena brings a knack for blending genres, here mixing period drama, farce, and dark humor. His decision to shoot on location in Tuscany lends the film an authentic, tactile quality, with the rolling hills and ancient architecture grounding the absurdity of the narrative.

The cinematography, by Quyen Tran, is understated but effective, using natural light and wide shots to capture the beauty of the Italian countryside. Close-ups are reserved for moments of emotional intensity or comedic payoff, allowing the actors’ expressions to drive the humor. The film’s color palette—earthy tones punctuated by the nuns’ dark habits—creates a visual cohesion that enhances the period setting without feeling stuffy.

Editing, by Ryan Brown, keeps the pace brisk, with sharp cuts that amplify the comedic timing. The improvisational dialogue requires careful editing to maintain clarity, and Brown’s work ensures that the film never feels chaotic, even during its wilder moments. The sound design is minimal but effective, with ambient sounds like birdsong and footsteps adding to the immersive atmosphere.

The score, composed by Dan Romer, is a highlight, blending medieval-inspired melodies with modern flourishes. The use of lutes and strings evokes the period, while subtle electronic elements underscore the film’s anachronistic tone. The soundtrack, including a few well-placed contemporary songs, adds to the irreverent vibe without overpowering the narrative.

One minor critique is that the film’s low budget occasionally shows, particularly in the limited scope of some scenes. However, Baena turns this limitation into a strength, focusing on character interactions rather than spectacle. The result is a film that feels intimate and grounded, even as it indulges in over-the-top comedy.

Cultural Context and Reception

Released in January 2017 at the Sundance Film Festival, The Little Hours arrived during a renaissance for indie comedies. Films like The Big Sick (2017) and Ingrid Goes West (2017) were showcasing the potential of small-scale stories with big personalities, and The Little Hours fit perfectly into this trend. Its blend of raunchy humor and arthouse sensibilities appealed to festival audiences, earning praise for its bold premise and stellar cast.

The film’s release came at a time when conversations about gender, power, and representation were gaining prominence, particularly in the wake of the #MeToo movement. While The Little Hours is not overtly political, its focus on female agency and its subversion of traditional period tropes resonated with viewers seeking fresh perspectives. The anachronistic humor, reminiscent of A Knight’s Tale (2001) or Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), also tapped into a growing appetite for genre-bending comedies.

Critically, the film received generally positive reviews, though some critics were divided on its irreverent tone. It holds a 78% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with praise for its performances and humor but criticism for its uneven pacing and niche appeal. The New York Times called it “a gleefully profane romp,” while Variety noted its “infectious energy” but questioned its accessibility for mainstream audiences. Box office returns were modest, with the film grossing just over $1.6 million against a $1 million budget, reflecting its status as a niche indie.

The film’s religious satire sparked minor controversy, with some conservative groups criticizing its portrayal of nuns and clergy. However, Baena and the cast defended the film as a lighthearted take on human nature, not an attack on faith. This controversy, while limited, added to the film’s buzz, cementing its reputation as a bold, boundary-pushing comedy.

Lasting Impact and Legacy

The Little Hours may not have achieved mainstream success, but its influence can be felt in the growing popularity of anachronistic comedies and female-led indie films. Its success at Sundance helped pave the way for other genre-blending projects, such as The Favourite (2018) and Emma. (2020), which similarly play with historical settings and modern sensibilities. The film also solidified Jeff Baena’s reputation as a distinctive voice in indie cinema, leading to subsequent projects like Horse Girl (2020).

For the cast, The Little Hours served as a showcase for their comedic talents. Alison Brie and Aubrey Plaza, already known for Community and Parks and Recreation, respectively, further demonstrated their versatility, while Kate Micucci’s breakout performance opened doors for more prominent roles. The film’s improvisational approach also highlighted the value of actor-driven comedy, influencing other low-budget indies.

The film’s legacy lies in its ability to make the Middle Ages feel immediate and relatable. By stripping away the pomp of traditional period dramas and focusing on the messy humanity of its characters, The Little Hours offers a timeless commentary on freedom, desire, and rebellion. Its availability on streaming platforms like Hulu and Amazon Prime has helped it find a dedicated audience, particularly among fans of offbeat humor and indie cinema.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths:

- Ensemble Cast: The performances, fueled by improvisation, are uniformly excellent, with Plaza, Brie, and Micucci forming a dynamic trio.

- Irreverent Humor: The anachronistic dialogue and bawdy comedy create a fresh, unpredictable tone.

- Thematic Depth: The film’s exploration of repression and agency adds substance to the laughs.

- Visual Authenticity: The Tuscan setting and understated cinematography ground the absurdity in a tangible world.

Weaknesses:

- Niche Appeal: The film’s irreverent tone and historical setting may alienate viewers seeking broader comedy.

- Uneven Pacing: Some subplots, particularly in the second act, feel rushed or underdeveloped.

- Budget Constraints: The low budget occasionally limits the scope, though Baena mitigates this effectively.

Conclusion

The Little Hours is a bold, hilarious, and surprisingly poignant comedy that reimagines the Middle Ages through a modern lens. Jeff Baena’s direction, paired with a stellar ensemble cast, creates a convent full of chaos, heart, and irreverent charm. By blending anachronistic humor with timeless themes of freedom and desire, the film offers a fresh take on period comedy that feels both subversive and accessible. While its niche appeal and occasional unevenness prevent it from reaching universal acclaim, its infectious energy and sharp performances make it a standout indie gem.

For fans of Monty Python, The Decameron, or contemporary comedies like What We Do in the Shadows, The Little Hours is a must-watch. Its snapshot of rebellious nuns and bumbling priests is as entertaining as it is thought-provoking, proving that even in the 14th century, human nature remains delightfully messy. Whether you’re drawn to its raunchy humor or its subtle heart, this film is a wild, joyful romp through a convent like no other.

Word Count: Approximately 3,000 words

Rating: 8.5/10

Recommendation: Ideal for fans of irreverent comedies, indie films, or anyone craving a fresh take on historical satire.